All posts by Avi Penkower

HOOVER AND HEBRON

Writing about any aspect of the Jewish-Arab conflict inevitably exposes the writer to charges of political leanings. While historians strive for objectivity, the readers of a blog typically are also interested in the blogger’s personal perspective. I hope that this post, and others I write, will inspire you to go learn more about a topic; to challenge my ideas, and be challenged by them in turn.

***

Where should a discussion of the 1929 Hebron attack against the Jews begin? I find it often useful to focus on individuals who trigger change and shape events.

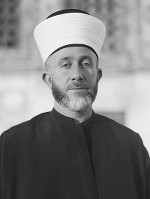

In 1921, Haj Amin al-Husseini was appointed Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, and he rallied Arab nationalism against nascent Zionism. In 1924, the Moslem Wakf began shedding doubt on the Jewish connection to the Western Wall, and in 1928 the Mufti claimed that the Jews were trying to take control of the mosques on the Temple Mount.

One week before the Hebron Massacre in August, 1929, a demonstration was held by the Jews to affirm their connection to the Western Wall. On Friday, August 23, inflamed by rumors that Jews were planning to attack al-Aqsa Mosque, Arabs attacked Jews in the Old City of Jerusalem. Rioting spread to the cities of Safed and Hebron, which both had a small Jewish minority.

On August 24, Arabs mobs attacked the Jews of Hebron. Armed with axes, knives and iron bars, they screamed “Kill the Jews!” They broke into homes and stabbed and mutilated the Jews they found. The mob included respected Arab merchants who killed their friends, clients, and business associates. Torah scrolls were burned. And while it is often stressed that many Arabs hid their Jewish neighbors, reliable accounts placed the number of such cases at 19.

Here you can read survivor testimonies; more details about the riots can be found here.

Sixty-eight Jews were killed, including a dozen yeshiva students from New York and Chicago; scores were wounded or maimed. Soon after, all of Hebron’s Jews were evacuated by the British authorities. Both Jews and non-Jews across the world were horrified by the massacre. The Shaw Commission was a British enquiry that investigated the riots; here is their description:

“About 9 o’clock on the morning of the 24th of August, Arabs in Hebron made a most ferocious attack on the Jewish ghetto and on isolated Jewish houses lying outside the crowded quarters of the town. More than 60 Jews – including many women and children – were murdered and more than 50 were wounded. This savage attack, of which no condemnation could be too severe, was accompanied by wanton destruction and looting. Jewish synagogues were desecrated, a Jewish hospital, which had provided treatment for Arabs, was attacked and ransacked, and only the exceptional personal courage displayed by Mr. Cafferata – the one British Police Officer in the town – prevented the outbreak from developing into a general massacre of the Jews in Hebron.”

President Hoover sent a message of condolence to the Jewish community; yet his personal correspondence on this matter was much cooler:

“I wish to thank you,” he writes, “for sending your very interesting observations on the situation in Palestine.”

I could end with observations on the shock of Hebron’s Jews who had maintained close relations with their neighbors for many years; on the fallacy of treating the Arab-Israel conflict as political and not theological, or on the obvious falsehood that the root of the conflict is in Israel’s occupation of Arab lands. Yet I prefer to leave you, the reader, to explore this topic, and draw your own conclusions.

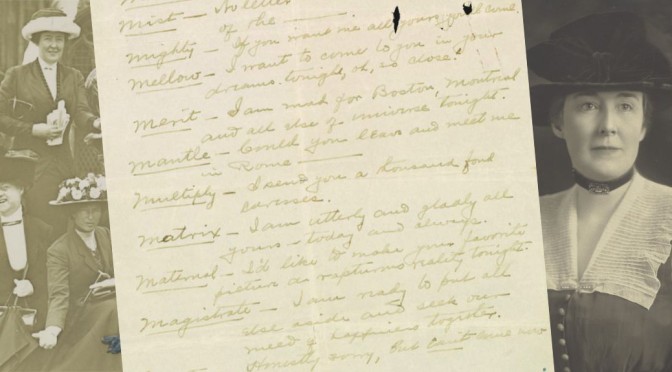

HARDING’S LOVE LETTERS

“I am not fit for this office and should never have been here,” President Warren Harding once conceded.

Harding served from 1921 to 1923 before he died in office. Perhaps his most memorable achievement was coming in last in popular polls ranking presidents, his administration was ineffectual and corrupt, culminating in the Teapot Dome scandal. On the personal front, he was far from a paragon of virtue.

In 1905, Harding was editing a newspaper in Marion, Ohio. One of his best friends was James Phillips, who owned a dry-goods store. In August of 1905, Harding began an affair with James’s wife – Carrie Fulton Phillips – an affair that would last more than 15 years.

Carrie Phillips kept all the correspondence between her and Harding – more than 1000 pages! Following her death, in 1964 the historian Francis Russell gained access to the letters, but the Harding family sued to halt their publication. A settlement was reached in which the Harding family donated them to the Library of Congress, but they remained sealed for 50 years.

50 years later, on July 29, 2014, the Library of Congress made the letters available to the public. They make for some pretty steamy reading:

“I love you more than all the world and have no hope of reward on earth or hereafter, so precious as that in your dear arms, in your thrilling lips, in your matchless breasts, in your incomparable embrace.”

They also shed some light on the rapidly evolving political landscape of the period; I strongly recommend you read the New York Times Magazine article on the subject.

Harding was long suspected of additional affairs; notably one with Nan Britton. Here you can see a personal letter from Harding, on White House stationery, on her behalf – rare documentation of their relationship.

TRUMAN ON THE BOMB

On May 8, 1945, the Nazi surrender ended the war in Europe, but the United States was still heavily engaged in what promised to be yet another protracted and painful conflict with Japan in the Pacific. Internal estimates of projected U.S. casualties predicted that some 400,000-800,000 American soldiers would be killed in the war with Japan. On July 26, 1945, in the Potsdam Declaration, the United States called for Japan’s unconditional surrender, threatening “prompt and utter destruction.”

On August 6, a mere 12 days later, the U.S. bombed Hiroshima – an industrial center with a large military headquarters – using a uranium atomic bomb; the first nuclear attack in history. 70,000-80,000 Japanese, including 20,000 soldiers, were killed in the attack; one third of the city’s population was annihilated. And as is the nature of nuclear warfare, within the first months after the bombing its effects ultimately killed approximately 150,000 people.

Following the bombing, President Truman declared:

“If they do not now accept our terms, they may expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth. Behind this air attack will follow sea and land forces in such numbers and power as they have not yet seen and with the fighting skill of which they are already well aware.”

On August 9th the Soviet Union declared war against Japan, and launched the Manchurian Strategic Offensive Operation.

Japan showed no signs of surrender.

The U.S. then dropped a plutonium bomb on the city of Nagasaki – a city with major war production industries; 60,000–80,000 were killed from the effects of the bombing.

Emperor Hirohito ordered his generals to “quickly control the situation… because the Soviet Union has declared war against us.” He authorized minister Togo to accept the terms of surrender, on the condition that he keep his position. In his declaration to the Japanese people, he added:

“Moreover, the enemy now possesses a new and terrible weapon with the power to destroy many innocent lives and do incalculable damage. Should we continue to fight, not only would it result in an ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation, but also it would lead to the total extinction of human civilization.

“Such being the case, how are we to save the millions of our subjects, or to atone ourselves before the hallowed spirits of our imperial ancestors? This is the reason why we have ordered the acceptance of the provisions of the Joint Declaration of the Powers.”

Historians and laypersons alike have debated the morality of the use of nuclear weapons, as well as the specific necessity of their use in the war against Japan – particularly after the Soviet attack. President Truman was adamant that it was the correct choice; in a letter he wrote the very day of the bombing of Nagasaki, he says:

“Nobody is more disturbed over the use of atomic bombs than I am but I was greatly disturbed over the unwarranted attack by the Japanese on Pearl Harbor and their murder of our prisoners of war. The only language they seem to understand is the one we have been using to bombard them. When you have to deal with a beast you have to treat him as a beast. It is most regrettable but nevertheless true.”

I do not wish to express judgment – the U.S. had just ended years of fighting against the Nazis, and faced another painful struggle with Japan.

Yet I wonder if the horror of war makes it inevitable that we dehumanize the enemy…

DAVID BEN-GURION ON “ALIYAH”

The story of Jewish immigration to the State of Israel (“Aliyah” in Hebrew) is unparalleled in history. When Israel declared independence in 1948, its Jewish population numbered 650,000; within three and a half years this number more than doubled by a huge influx of 690,000 immigrants. From 1948 to today, more than 3.5 million Jews immigrated to Israel.

For thousands of years Jews living in all corners of the globe dreamed of returning to their national homeland, and when the opportunity arose, they responded – albeit in varying degree. Broadly speaking, Jews living in Arab countries left en masse, while Jews from more democratic countries immigrated in smaller numbers.

Jews from North America tend to immigrate to Israel more for religious or ideological reasons, and less for financial or security ones. During the early decades of Israel’s existence a few thousand North American Jews immigrated and stayed, but this number leaped following the Six-Day-War. Between 1967 and 1973, 60,000 North American Jews immigrated to Israel.

Today, an organization called Nefesh B’Nefesh promotes Aliyah from English-speaking countries by providing financial assistance, employment services and streamlined governmental procedures. Their flagship events are charter flights full of immigrants (Olim) every summer, which are greeted by IDF soldiers, friends, and family, and are widely broadcast in Israeli media.

Aliyah has always been a big deal in Israel, and from the early days of the State, Israelis would ask Jews the world over – Nu, so when are you coming?

A month after the Six-Day-War, a well-known David writes to a lesser-known Ruth:

“Our country was built by three generations of pioneers, and it is not yet finished – it is only a beginning. We must get a large immigration from the free countries, mainly from the United States, to take part in its building – it will take at least another generation or more.

“When are you coming to Israel?”

THE ROUGH RIDERS

How many Americans today know about the Spanish–American War of 1898?

The late 1890s saw widespread anti-Spanish propaganda and yellow journalism, led by Joseph Pulitzer of the New York World and William Randolph Hearst of the New York Journal. Many Americans saw Spain as a classic oppressor in Cuba, and viewed the struggle for Cuban independence as a parallel of their own, one century earlier.

The United States also had deep financial investments in Cuba, and annual trade (primarily in sugar) was over $100 million. And while President Grover Cleveland declared neutrality in 1895, by 1898 the national climate had shifted. On February 15th, a mysterious explosion sank the U.S.S. Maine in Havana Harbor and 266 American sailors were killed. The U.S. Navy declared that a mine destroyed the Maine; President McKinley ordered a blockade of Cuba, and on April 25th the U.S. declared war.

The US Army was still severely weakened following the Civil War, and President McKinley called for volunteers to aid in the war efforts. The 1st United States Volunteer Cavalry was the only one of three volunteer regiments to see action; they are far more recognizable by their other name – the Rough Riders, led by Theodore Roosevelt. (Roosevelt resigned his position of Assistant Secretary of the Navy to join the volunteer cavalry, to great acclaim.)

After fierce fighting, Spain and the United States signed a peace treaty on December 10, 1898. The Treaty of Paris, negotiated on terms favorable to the U.S., allowed temporary American control of Cuba, and ceded authority over Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippine islands from Spain.

The war had cost the United States $250 million and 3,000 lives, of whom 90% had perished from infectious diseases. Both the preparations for the war and its aftermath took a harsh toll on many of the volunteers; here you can see Theodore Roosevelt describing the suffering of the Rough Riders, weeks after the crucial Battle of San Juan Hill.

A JEWISH REFUGE IN… PERU?

“Einstein is, you know, not a Zionist,” Kurt Blumenfeld wrote to Chaim Weizmann…

In 1919, just after the end of the war, anti-Semitism in Germany was worsening, the necessity of a Jewish homeland was becoming terrifyingly clear, and Prof. Albert Einstein was becoming world famous. What better time for the German Zionist Federation to approach Einstein for his support?

The group’s secretary, Kurt Blumenfeld, tailored his description of Zionist projects to fit Einstein’s interests—as did Chaim Weizmann, himself an accomplished scientist and the future first president of Israel. When Einstein joined Weizmann on a major fundraising trip to the U.S. in 1921, he said little about his own views to American audiences, instead urging them to follow Weizmann. As described in Ze’ev Rosenkranz’s fascinating book Einstein Before Israel(Princeton University Press), Einstein’s relationship with the Zionist movement, and with Jewry in general, was complex.

Yet there is ample evidence that Einstein was quite concerned with the fate of Jews in danger; here we can see first-hand evidence of his efforts to help relocate some 20,000 Eastern European Jews – Jews who had fled to Berlin during the First World War, and who were now stranded there. What nation would give them refuge? The gates to Palestine were tragically closed…

It seemed like a good idea (he wrote) – a Jewish refuge in… Peru. And he added, somewhat cheekily, “My name has certain advertising powers when it comes to Jews.”

No comments:

Post a Comment